carlmeek 23-Mar-22 06:19 28

I don’t think this is an issue at all. The inputs are actually not different.

I disagree. If you push the cyclic forward as aggressively in a helicopter as you must push the stick in an aeroplane on losing power at Vx, the result is not going to be good.

" I disagree. If you push the cyclic forward as aggressively in a helicopter as you must push the stick in an aeroplane on losing power at Vx, the result is not going to be good"

That is certainly the case in a lightweight like the R22 but it is not necessarily the case in a Gazelle, or a Lynx.

That is certainly the case in a lightweight like the R22 but it is not necessarily the case in a Gazelle, or a Lynx.

Can those types fly a ballistic (0 g) flight path, or even some negative g?

Teetering rotor systems are the worst for low g mast bumping, but unfortunately those are also the most common/affordable GA types.

That is certainly the case in a lightweight like the R22

Or indeed a Huey, not generally considered a lightweight.

As I understand it, there are two main issues regarding putting rotorcraft in low-G situations. One is mast-bumping, and the other is that in autorotation you can reduce rotor RPM to unrecoverable levels. A heavy rigid-rotor is going to provide a greater margin in both respects.

This article emphasises the importance of aft-cyclic in autorotation. The FAA handbook also states that you need to apply aft cyclic on entering autorotation. I chatted to some reassuring autogyro pilots at Kirkbride a few weeks ago, but still worry that my get-the-nose-down reflexes are too highly developed for me to ever fly a rotorcraft safely.

In the gazelle – assuming that you’re at cruise speed of 118 knots, if the engine fails you are carrying quite a lot of energy. if you drop the collective and pull the cyclic back you’d overspeed the Rotor RPM rather quickly – pulling back effectively flares off your forward speed and converts it to rotor RPM. In this scenario – with rotor RPM in the green, and carrying excessive speed, there would be nothing wrong with pushing forward – it would be the strategy you’d use to stretch the glide to the furthest distance – the furthest glide is achieved with low RPM (Still in green – low end) and high airspeed. If you wanted to glide to somewhere closer, you’d be pulling back, and lifting the collective to ensure it didn’t overspeed.

Horses for courses of course – I’ve never flown a teetering head 2-blade helicopter.

Day 3

Things we covered on the first two days are more relaxed items now. The meat and drink of the day are transitions. Transition to forward flight, and transitions from forward flight to the hover. The helicopter has a preferred take-off profile that provides the best chance of an autorotation if it is followed. It’s called an avoid curve, not a prohibited curve. It’s a bit like flying a twin into a short grass strip in the fixed-wing sense. You can go outside the recommended practices in the POH if you are happy to live with the consequences in the event of an engine out. In helicopter training, you fly the take-off and landing profile that keeps you safe. In the real world, you may be going into a hotel car park from a high hover, and that is something for the owner to decide to take a view on.

From a stable hover at say 24" MP and 3100rpm, you push forward on the cyclic. It feels like the helicopter is going to nose into the ground, but you have to continue to push forward as the blades encounter “flap back” … and push again as the blades encounter “translational lift”. About 180m from where you started you are doing 52kts and climbing away to join a circuit. Pushing forward twice to take off with the cyclic is very different to fixed-wing.

Do a circuit and once established on a final, you target 50kts and about 16" of MP flying the approach like a fixed-wing. Coming over the hedge reduce the collective to about 14" MP and slow down to about 40kts adding right pedal. Coming to the aiming point in the centre of the field, pull collective as required, add left pedal to keep your heading and throttle as required to come to a hover ideally about 6 ft up. There is a lot going on in a tight low circuit, and it’s a busy affair compared to fixed-wing. Going off-airport and practising this into carefully selected places is the best fun of the course so far. Site selection is a lot like seaplane flying and wires/houses/animals/wind/approaches all coming into the site assessment. These need to be second nature to you.

To go in three days from preflight, startup, hover, pedal turns, hover taxi, transition to forward flight, climbs, turns, descents, transition into the hover and landing means much of the basics are covered. There is a lot more to learn, and I think you could fly it every day and still learn something. We obviously have another 30hrs of the PPL course to fill with learning items. As per the EASA guide on the matter, there is a target guide for learning progression.

Thank you for these reports. They are really interesting. I have flown helis but only a very tiny amount, and no hovering.

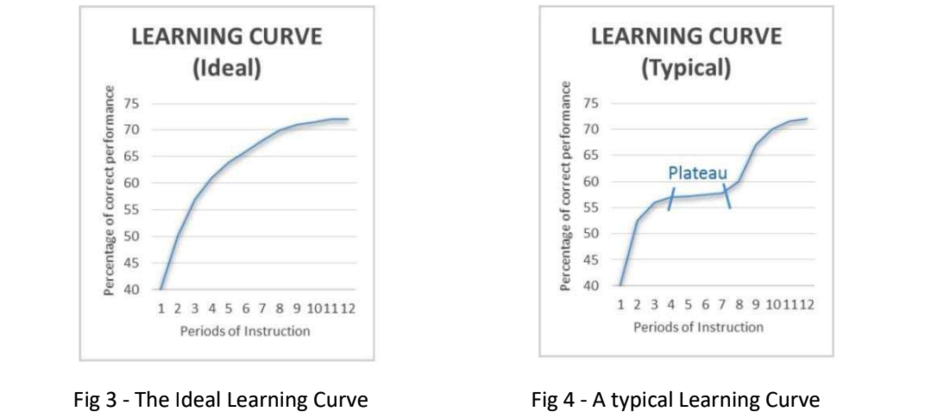

That 2nd learning curve probably applies to a lot of things. It definitely applies to various sports (IME, windsurfing, water-skiing) and it also happens in PPL training and particularly landings where most people go through bad patches.

Peter wrote:

That 2nd learning curve probably applies to a lot of things. It definitely applies to various sports (IME, windsurfing, water-skiing) and it also happens in PPL training and particularly landings where most people go through bad patches.

“Plateaus” are the largest problem for any kind of attempted achievement, from learning things to loosing weight to sports or playing musical instruments e.t.c.

The duration of those are largely different up to the point where people regress and eventually give up. Recognizing the plateaus and dealing with them is what I think is the real challenge in coaching or instructing. The main thing is to finally find out if you are dealing with a plateau from which the curve will eventually start to go up again or have you reached the capacity of the individual and will have to come to terms with the fact that for that individual the aspired goal is not achievable.

Lots of training organisations in many places make a lot of money with people who remain in a “platau” forever, where the consequence should be to stop training for lack of progress. In the old days of sponsored flight training, plateaus killed more aspiring airline- and military pilot careers than anything else. Today it is mainly the question of how much more cash is available to dump into instruction which decides when to stop training or whether to simply continue indefinitely until cash runs out.

Thanks a lot @WilliamF for this detailed write up on your progress. Really interesting to read.