This is always the conventional wisdom i.e. a slower speed produces a tighter turn. It’s obvious.

But – in a given aircraft – a higher speed increases Vs so you can pull more G when you turn.

I don’t know how to work this out, but don’t these things cancel out? Obviously max airframe loading will be one limiting factor.

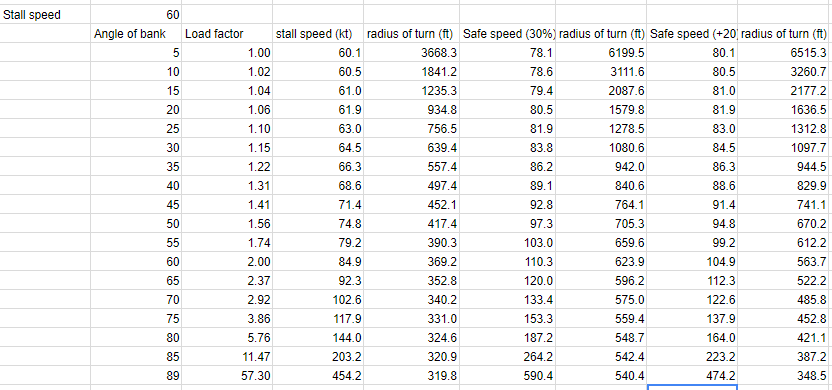

This is the sort of thing I have in mind:

Lots of things are possible. You can do a lazy eight kind of turn for instance (normal in a Cub, and it’s a very tight turn), and further, a full stall turn (not very normal in a Cub  ) But IMO, pulling lots of Gs requires lots of speed and/or lots of power, F-16 kind of speed/power, so it is outside the envelope of normal GA.

) But IMO, pulling lots of Gs requires lots of speed and/or lots of power, F-16 kind of speed/power, so it is outside the envelope of normal GA.

I’ve plotted the radius of turn below. Higher bank (requiring higher speed if straight and level is to be maintained) would give you a tighter turn.

One extreme is if you are at stall speed, then you can’t bank and can’t turn, so your radius is infinite. On the other end, you have a very tight radius, but you die because of G forces.

edit: fixed an error in a formula

Radius is V^2/(11.26*tan(bank angle)) so yes for a given bank angle the radius decreases. You can compensate by bank angle but as Noe says then stall speed becomes increasingly limiting.

Peter wrote:

This is the sort of thing I have in mind:

Reminds me very much of this accident here: https://reports.aviation-safety.net/2010/20101219-0_PRM1_D-IAYL.pdf

They did a go-around in poor weather at Samedan, followed by some sort of “visual” pattern. The only thing they clearly saw were some rocks ahead so they tightened and tightened their turn at low speed until they fell out of the sky.

After that accident our then type-rating-examiner made us do a paper-and-pencil calculation before every checkride in which we had to determine the minimum height above a valley floor which was required before one can safely fly a turn within the width of the valley (increasing with height usually). A good exercise for every pilot every now and then and a real eye-opener for some. (And avoids the hassle of the mandatory report I would have to submit after getting a “pull up! pull up!” during a downwind turn…)

The conventional wisdom in canyon flying (In my experience) is slow speed and some flap. So in the 172 this means 70kt and 2 stages. It gives a very impressive turn radius. Not quite the turn radius point that Peter’s making, but in a canyon situation it’s vital to make any turnback decision as early as possible, and so it’s important not to consume the available terrain with too much speed along the canyon. Anyway, you’re there for sightseeing, not because the cloud is on top of the mountains, right?

A vital consideration in canyons is keeping good visual orientation. Once the true horizon is out of sight behind ridge lines it’s easy to become misled and steep banking makes this much more likely to happen. The visibility in a high wing is also a factor, making ground reference features more difficult to keep in sight as the bank winds up.

Shadows are also a big factor, and the higher the speed, the harder it is to discriminate what is shadow and what is rock! Not just whole mountains within the valleys in British Columbia becoming invisible at low sun angles (yes, that really happens!), but also sharp rock pinnacles that can hide in the shadows close to canyon walls in Arizona.

US private training features turns around a point and these are taught quite aggressively, pointing the wingtip directly at a ground reference and keeping it there, again with a view to a box canyon situation. Much easier to do at low speed and different from UK training, in my time at least.

Finally, it’s easier to avoid a big bird at low speed in a canyon. Although actually, the bird, who I thought momentarily was a falling rock, was chasing me (in a 152 with rear windows) and I had to open up to get away!

In canyon flying, you want to be close to the mountain on one side, so you have the maximum room for a turnaround the other way. Seems obvious, but many tend to stay in the middle away from the perceived danger. Also, if you can trade altitude in turn, you can tighten your turn considerably. The Box Canyon Turn is a combination of a tight turn and a wing-over, and is probably the tightest turn you can do without trading too much altitude. Full power, nose up to slow her down, full flap, bank to 60 degrees. At 45 degrees, release all back pressure and let her “fall” into the turn. As you come out of turn at around 45 degrees of bank, restore back pressure to arrest descent.

Adam’s quite right about staying to one side. Another reason is the air currents – air will be falling on the shadowed side, so that’s the place to be so that the turn will be into rising air on the sunlit face. Notwithstanding the hidden rocks and aggressive defensive birds!

I’ve not tried the “diving to the canyon floor” technique!

Theoretically, the min radius is achieved at a bank angle corresponding to the maximum G allowed by the airplane, and with the minimum required speed, which in that situation is Va.

If you go slower then you’re not maximizing the centripetal force

What is a “full stall turn”?