Operational Tips for VFR and IFR in Europe

(work in progress)

This article attempts to compile various tips which are not generally taught

but which can make a difference between flying being straightforward and being

a lot of hassle.

Flying itself is normally very enjoyable, but – in Europe especially – there

can be a great deal of bureaucracy on the ground, and it is the ratio of the

enjoyment to the hassle which determines how long a pilot will hang in there

before giving up flying for good. There is limited scope for improving the flying

part but reducing the ground hassles is relatively easy.

Approach / Airfield Plates

VFR pilots tend to use national publications such as Pooleys

(UK). These are fine but are rarely published for the more southerly European

countries. Jeppesen used to sell huge VFR guides under the “Bottlang”

name but these have been replaced by the VFR version of their Jeppview product

which is available in both paper and electronic versions. For much of Europe,

this Jeppesen product is the only game in town, but it is often out of date

(particularly for countries where GA activity is low/negligible i.e. most of

Europe) and good information can be obtained from the local AOPA. An excellent

example is the Greek

AOPA which has up to date information on its website.

For IFR pilots, Jeppesen’s Jeppview is the worldwide standard

and provides a uniform presentation throughout. Unfortunately, due to a lack

of competition in Europe, it is very expensive here; around 2000 euros/year.

Jeppesen split up their coverage between Western Europe and the old Communist

Europe and what they call “Europe” is only the former bit. This product

can be delivered in paper (impractical for more than maybe 1 country, due to

the time spent in inserting each month’s updates) or electronic (CD or download)

versions. Within the terms of the Jeppesen license, there are some limited options

for sharing the cost with other pilots, e.g. it can be installed on up to 4

computers. It is however obvious that a flying club etc can purchase a copy

too.

Jeppview can be used to display the plates, and they can be printed. It runs

under Windows only i.e. on a desktop PC, or on a tablet computer running Windows

in the cockpit. There is no way to run Jeppview on an Ipad, but Jeppesen have

recently announced a cut-down viewer application for it.

Other option, for Europe except Greece, for both VFR and IFR, is in the form

of nationally published plates, which are within each country’s AIP.

These are mostly drafted for A4 printing and are not as convenient or concise

as the Jeppesen ones. They are produced to comply with ICAO obligations, not

to be particularly usable by pilots, but they are free! They usually do not

show the decision height directly; it has to be calculated from other data.

These can be downloaded from the national

AIP websites or from the Eurocontrol

EAD site.

Some older players in the IFR plate business include Aerad (formerly owned

by British Airways) and some obscure publishing operations run by large airlines.

However, as far as I can tell, none of them offer electronic delivery, or any

advantage, pricing or otherwise, over Jeppesen.

Reducing the cost of approach plates and GPS databases

The AIP plates are free – in PDF form from Eurocontrol or national AIP

websites.

For Jeppesen plates, most users have moved to the electronic format,

sold as Jeppview 3. Methods of reducing the cost of this data all involve sharing

it among a number of people, but most of these contravene Jepp’s Ts & Cs:

A subscription for a panel mount product (e.g. a GPS or an MFD) can (obviously)

be shared among all people who fly the aircraft. This appears to be the only

100% legitimate way of sharing Jeppview approach plate data.

A standard Jeppview 3 PC subscription can be installed on up to four PCs. These

are supposed to belong to the same person, but this obviously cannot be controlled.

This can be used to split the cost four ways, with each person having his “own”

program on a laptop etc. This is the only really convenient way.

A standard Jeppview 3 PC subscription can be installed on a PC located in a

flying club, a hangar, etc and anybody present can print off plates as required.

This can be used to split the cost any number of ways. There are indications

(reported by people who have contacted Jeppesen and asked the question) that

Jeppesen are not particularly bothered about this kind of usage, and it is widespread.

A standard Jeppview 3 PC installation can print approach plates to PDFs, which

can be emailed, etc.

It is easy to think of other ways e.g. installing Jeppview 3 on a PC running

a remote desktop server product, which can be remotely accessed by a number

of people running the remote desktop client. Each person would login, print

the plate(s) to PDF(s) and email those to himself.

For GPS databases (which nearly all originate from Jeppesen), there is a somewhat

cunning and 100% legitimate method which relies on someone being happy to fly

with data which is 1 cycle late: when you update your database cartridge, pass

the previous one to another owner of the same GPS. With the data being updated

every month, the chance of a pilot flying “conventional IFR” discovering

a problem (due to e.g. a deleted waypoint) is extremely small, would be detected

when loading the flight plan, and could happen anyway because the updates may

not be delivered the instant they become current. In this way, one could set

up a group of pilots of which 1/2 flies on 1 cycle late data (and pays slightly

less than 1/2 of the total cost, to keep it fair). One could pass down the 1

cycle old data even further; many pilots – especially IMC Rated ones – have

little need for the latest Eurocontrol airways waypoints and many pilots rarely

if ever update their GPS databases anyway. This technique works with most GPS/MFD

products which lock the database download to a key stored on the data cartridge

itself, so the cartridge can be passed to somebody else. It definitely works

with the KLN94 (which uses a hacked CF cartridge with a unique key on it), with

the KMD550 MFD (whose 20MB linear flash cartridge is not keyed and they just

rely on the equipment

to read/write it being too obscure and pricey) and I think it works with the

Garmin GNSx30/W products (which use a proprietary flash cartridge with a unique

key on it).

Flight Planning Software

VFR pilots have a choice of several products. The longest

established pan-European program is Navbox;

this very basic program has remained virtually unchanged for at least 10 years

but it provides the functions to draw a route using click and rubber-banding

and then print out a wind-corrected plog. It has a good coverage of Europe and

its data is very reliable, but it has only very bare mapping data so needs to

be used together with VFR charts. I used Navbox for all my pre-IR VFR trips

around Europe. There are several other products around Europe; German pilots

have this very slick VFR planner which

includes directly usable VFR charts. Jeppesen’s VFR flight planner is FliteStar

VFR but it is not widely used, partly due to the complex interface and feature

set, and partly due to the price. FliteStar does not come with map data adequate

for VFR flight unless one purchases the Raster Charts add-on; this is an over-compressed

JPEG version of its 1:500k “VFR/GPS” paper charts which can be viewed

and printed within FliteStar but cannot be automatically printed as a series

of enroute chart sections, which is a great pity, as the single CD covers most

of Europe. Finally, there is the new and very good looking SkyDemon

which I don’t know anything about except that it doesn’t have a full European

coverage.

IFR pilots have just one program which supports airways in

a useful manner: FliteStar

IFR. It has a rudimentary route generation facility but the generated routes

rarely pass Eurocontrol validation. If you have a validated Eurocontrol route

from elsewhere, it can be pasted into FliteStar’s “plain language”

entry feature, and then completely usable enroute IFR charts can be printed

off, together with the plog, etc. This trip

report illustrates the procedure. However, for IFR flight done in controlled

airspace and under ATC direction, one does not need super quality mapping data,

and the FlightPlanPro IFR route

generator can produce cockpit material which is usable alone. In principle,

any “VFR” flight planning program capable of displaying airways can

be used to generate a plog and possibly enroute chart sections for an IFR flight,

but the process tends to be torturous; I have tried it a few times in Navbox.

It can be argued that, reflecting standard IFR ATC practice, all one needs

is a list of waypoints and enroute charts are not needed. This is true most

of the time, but I have been given airway names on several occassions, and having

a picture of the route ahead helps to keep ahead of the game when ATC send you

to a waypoint which is not on your list. It also helps when asking ATC for shortcuts;

a shortcut across several waypoints that lie in a straight line is not worth

asking for.

IFR flights which contain VFR sections, e.g. Z or Y

flight plans, and I flight plans involving airports outside

controlled airspace, or any IFR flight where the IFR clearance is not runway-to-runway,

require the availability of proper VFR charts. This can be a nasty little trick

for e.g. an American pilot who flies everywhere “IFR”; upon arriving

in Europe he finds he has to fly around for possibly many miles, at some low

level below controlled airspace, before collecting an IFR clearance and getting

a climb to where he wants to go.

Charts – VFR

Everyone has their preference but I think a few comments can be made:

For the UK, the CAA 1:500k charts (example)

are excellent – clear and unambiguous as regards airspace class and vertical

extent.

The CAA charts are also marketed in electronic form by Memory Map and can then

be run as a GPS moving map on a suitable Windows (or Windows Mobile) platform.

Unfortunately, for 2010, Memory Map has moved to a tight machine-specific licensing

system which makes this product hard to recommend.

France offers several good options: the 1:1M SIA charts (example

– very readable and compact to use in-flight, but require the use of a supplied

booklet to work out vertical extents and operating hours of danger/restricted

areas); the 1:500k IGN charts (even more readable but show nothing above

approx 5000ft, which makes them next to useless for serious touring); the 1:500k

Cartabossy charts (example – perhaps the best

option if you don’t like the SIA booklet). I fly with the SIA charts; they are

often regarded as the most “official” for France but a sharp reader

will spot a glaring error in the example above, in the Class A airspace to the

SW of the Isle of Wight…

France, and much of Europe including the UK, is also covered by the Jeppesen

1:500k “VFR/GPS” charts (example).

These are less than ideal as to ambiguity of airspace depictions but offer consistency

and are preferable over many locally-issued charts, some of which are of poor

readibility.

Some nationally produced charts are good (e.g. German ones) but not many…

The Jepp 1:500k charts are also available in an electronic form called “Raster

Charts”. These are in a proprietary format which can be viewed only in

FliteStar. They cannot be run as a GPS moving map, except in a version of FliteStar

called FliteMap, which was taken off the market in 2005. However, somewhat out

of date versions of these Raster Charts are widely available on the bit torrent

scene, in Oziexplorer format. The quality

of these is not great, due to heavy Jpeg compression.

Further afield, beyond the coverage of the Jepp VFR/GPS charts, the only option

is likely to be the U.S. produced ONC/TPC charts (example).

These were last updated c. 1998 and do not show controlled airspace. They show

danger areas but these are obviously out of date. They are available from various

outlets e.g. here,

and from here

in various electronic versions ready for use under e.g. Oziexplorer.

For Greece, the only VFR chart was the ONC G3 one (1998) which is obviously

useless except for basic topographical and airport-location data, but in 2011

a group of Greek pilots produced a set of two excellent charts, based on the

ONC/TPC topo data and depicting the current CAS etc; these can be bought here.

They also do an Ipad version which can be bought from the Apple shop.

There is no need to carry VFR charts on IFR flights – except when any

part of the flight is going to be outside controlled airspace, and that is true

for many GA flights even when filed as I.

Charts – IFR

Jeppesen and Aerad publish printed enroute IFR charts. They are also mailed

out with the CD subscription to Jeppview. I no longer use these huge unwieldy

and difficult to read things (they are great when stuck on windows, as sunscreens)

because the A4-printed IFR chart sections from FliteStar (example)

are fine.

Flight Plans

There are common misconceptions about what a flight plan actually does.

A flight plan is just a message, addressed and delivered to specific addresses

which are usually the airports of departure and destination. In between, nobody

sees it. Actually, the flight plan does get copied to various databases for

“national security” reasons – most countries make some effort to keep

an eye on air traffic crossing their borders – but nobody of relevance can access

it there. Think of it as an email. There is no way to know if anybody actually

got it, and there is no way to know if anybody actually read it.

Flight plans are mandatory when crossing national borders – even within the

Schengen area. For all other flights they are optional (in Europe, generally)

but are arguably worth filing when crossing remote areas, etc. Flight plans

are also mandatory for most flights in controlled airspace but these situations

are normally dealt with by the radio call asking for the transit clearance;

this radio call constitutes an “airborne” flight plan.

With very few exceptions, a flight plan does not constitute a PPR/PNR

request message. There is no logical reason why this should be but that is the

way aviation works. Job demarcation is often strict and when Tower/ATC staff

receives a flight plan they are highly unlikely to copy it downstairs to the

Operations department which is in charge of permissions, or to Customs so they

can expect the flight, etc.

A VFR flight plan does almost nothing except provide some hint of where

to look for the wreckage if you go missing. In Europe, generally, you could

file a flight plan with a waypoint in Kathmandu and nobody is likely to notice

that the route is meaningless. Some UK pilots do indeed file VFR flight plans

with names of villages, etc, in the route. A VFR flight plan is not acknowledged

in any way, so hearing nothing back does not mean the destination airport is

even open, etc.

An IFR flight plan is normally addressed to Eurocontrol (also called

IFPS or CFMU) and from there it is distributed to relevant enroute units, usually

about 5-10 hours before the filed departure time. An IFR flight plan is acknowledged

by Eurocontrol but this merely means the computer doesn’t object to it; the

departure and landing times could be outside the airports’ opening hours, etc.

It is also easy – particularly in the UK – to file IFR flight plans which start

and end in low level Class G and which bust loads of Class A and all kinds of

other stuff along the route. When flying “IFR” within UK Class G,

an IFR flight plan does nothing more than a VFR one.

Some notes on how flight plans work and how to file them are here.

Planning

The internet has revolutionised more or less all preflight

activities. Weather data, airport information, etc are all on the internet.

Flight plans can be filed electronically.

Even the black art of IFR Eurocontrol route development, maintained as such

for so long while keeping expensive business jet flight support services (e.g.

Jeppesen) in business, has now been solved with software tools – FlightPlanPro

being the latest one. Eurocontrol eventually capitulated and started offering

their own “route suggest” facility; this is not usable directly but

can be accessed via FlightPlanPro and EuroFPL.

The route itself can be constructed using a variety of programs. The result

can be printed out – when away from home – on a small portable printer, or even

loaded directly into a display device such an e-book reader or a tablet computer.

But you need mobile internet access which is reliable; wasting

hours looking for an internet cafe doesn’t count. The whole job needs to be

doable from the hotel room so one can head straight to the aircraft with no

delays. Some notes on mobile connectivity are here.

What remains is dealing with airport bureaucracy; specifically obtaining permissions

for various things. Many airports in Europe need prior permissions (PPR) or

prior notifications (PNR) and this disease is spreading. The published contact

data is often duff and the further one goes south the worse it gets. The most

common one is Customs PNR (also called “Customs O/R – Customs On Request”)

where the local police need to be notified of an incoming or departing flight;

Most of the time they don’t turn up but some airports, notably in Spain, Greece

or Italy, and absolutely in Turkey, will refuse a landing if the specified PNR

or PPR notice period is not complied with.

First, for IFR, get the airport notams. Many

IFR pilots, flying in controlled airspace under radar control, do not get enroute

notams and this is reasonable, because route acceptance by Eurocontrol – assuming

the flight plan was filed shortly before the flight – has already checked for

closed airways, etc. But airport notams are in a different category and should

always be looked at. Most PPR/PNR airports do not notam this requirement but

some do, and the notam will reveal other potentially important stuff like a

defunct ILS, resulting in much increased minima. VFR pilots

must obtain enroute notams for the entire route, because a

radar service may not be continuous, or may not be available at low levels.

Unfortunately, notams cannot be relied on for vital information of a long term

nature (e.g. avgas no longer stocked) because they are cancelled as soon as

the information is published in the AIP.

Next, contact the airport with a few questions: PPR/PNR,

Avgas, Customs, opening hours. If the aircraft is non-EU registered,

make this clear as in some countries the “treatment” differs (e.g.

Turkey is 24hrs PPR for these). If possible, this process needs to be kicked

off a few days before departure, especially if going further south in Europe.

The following notes are written with emphasis on avoiding handling agents

(the traditional light GA approach) which involves contacting the airport directly.

There are several ways to find airport contact details (telephone/fax/email).

A google on “xxxxx airport” usually reveals the airport website. However,

for most large airports, there are no GA contact details and those shown do

not work. Other methods are: Navbox (quite

good), Jeppview (less good), national

AIPs (variable)…

The ACUKWIK airport directory (available

as a book, a CD, or online with a limited-scope free section) is a good tool,

and is most reliable on numbers of handling agents who are usually delighted

to “handle” your flight; one can then ask for a contact number for

the airport GA office itself. If however the airport operates mandatory handling,

then the handling agent should be able to arrange everything needed (see notes

below on Handling) and there is no need to contact the airport.

Another great online airport directory, which is free, is the Handbook

of Business Aviation.

Warning: do not use any airport directory as a definitive source on

whether an airport has Customs, Avgas, etc. Use it only to get contact details.

The first contact option is to telephone. If this works in

English, or you can speak their language – great. If this is not successful

then email or fax is the next option, but you may not get a reply for a few

days.

In some cases a written contact is desirable: if the airport is PPR, or Customs

are PNR, etc. In southern Europe in particular, always get the permission in

writing (fax/email); in this context, PNR=PPR because you need a confirmation

they have received the PNR! I have been refused a landing clearance in Italy,

had a flight plan cancelled by a destination airport in Spain, and I know of

Corfu LGKR refusing several inbound flights because the PPR was arranged verbally.

A large part of the contacting problem is that while ATC at international airports

is required to speak English (to a degree, anyway), there is no such requirement

on office staff. I remember spelling Alpha Victor Golf Alpha Sierra to

someone at Pamplona (Spain) before giving up and flying elsewhere. Pamplona

did list Avgas but in this kind of situation only a fool would chance it. I

am sure you could improve the odds greatly by getting someone to translate,

but the reply will then come back in the local language and you have to translate

that also. Google translation doesn’t really cut the mustard – yet.

Regarding fax or email, my experience is

that fax works if you send your message to more than one fax number published

for that airport! Published email addresses rarely work; not because the GA

office is not on email but because email addresses tend to go out of date quickly

so the published ones are often wrong. Plus, emails tend to get caught by spam

filters, etc etc. I get good results by emailing several published email addresses,

and also faxing the same message to a few numbers. This is efficiently done

with an email2fax service (I use Interfax)

by using both the TO and BCC fields concurrently:

The above example contains several time-saving tips. The message is faxed using

email2fax using the BCC field (the @fax.tc is a particular method used by Interfax).

Because faxes do not have a Subject header or a return address like an email

has, all this stuff has to be repeated in the body of the message. Declaring

that everybody is an EU citizen is likely to lead to Customs not even bothering

to turn up. Declaring the tail number as US registered (in this example) could

conceivably increase the risk of issues through someone not liking U.S. foreign

policy (something which no airport will admit to openly, although I was asked

to pay 48 euros for being N-reg at LGMT, before they changed their story) but

it ensures that any problems surface earlier rather than later.

The title “Captain” would attract instant ridicule in the GA community

in northern Europe but it commands respect at larger airports everywhere. A

pilot uniform is highly recommended if travelling outside Europe, for the same

reason; it commands instant respect.

Any email should be sent in plain text, not HTML. Make sure your email

program is configured to send emails in plain text only, and avoid fancy

stuff like underlines, bold, font changes, and colours. Many people do not use

Micro$oft email software and cannot read HTML-only emails. Avoid sending attachments

on the initial contact.

Your own fax number, supplied in the message, obviously needs to work. The

most practical way is a fax2email service; Interfax offer this too but I use

Edge Telecom which is

much cheaper. When setting up such a service, avoid non-geographical numbers

(0870 etc) because these cannot be dialed from many foreign countries. It is

much better to pay a bit extra for a geographical number (e.g. 01273; Brighton).

Many “modern” people, immersed in a world of email and instant messaging,

dismiss fax as ancient but it remains widely used in aviation and international

business generally. In the context of obtaining PPR, a fax is by far the easiest

way to transmit a rubber-stamped or signed document, and almost every PPR confirmation

I have received was delivered by fax even if other comms with the same person

were done by email.

I have had very good success with the above email+fax approach. The contact

details in the reply are very useful in later flights, of course.

Another possibility for contacting an airport is an AFTN message.

This is possible using the AFPEx

tool, which is available to pilots with a UK address. A Free Text message (use

the same content as the above email/fax example) is delivered instantly via

the AFTN network. The message can be addressed to xxxxZTZX (Tower), xxxxZPZX

(Planning Office), xxxx YOYX (AIS – the office where a flight plan is handled).

In the foregoing, xxxx is the airport ICAO code. I send it to the first two;

the 3rd one is a recent discovery, but at many airports all these end up on

the same terminal. With big airports, this really should work 100% but I have

found the response rate to be poor – presumably due to airport job demarcation

and other dubious working practices. Also, many smaller airports are not directly

on the AFTN; the messages are diverted to another one which then faxes them

over. And many small airfields have no AFTN access at all. When I did get a

reply it was always by fax or email. Finally, since AFPEx does not offer a copy

of incoming messages to email, you have to start up the application to check

if any replies have arrived. I now think that AFPEx is a waste of time, except

for a straight flight plan filing.

Some airports probably get fed up with pilots sending multiple messages but

they have only themselves to blame for poor organisation. Many airports are

bastions of 1970s working practices.

If flying to Italy, specifically check that they have avgas

and will sell it to a visiting pilot, anytime during their opening hours.

Many airfields there do not sell avgas to visitors. Unfortunately these airfields

may show as “having avgas” in the published data… Italy has acquired

quite a “reputation” for hassle over the years, which is probably

unjustified for Italian speakers who can simply telephone, and variously justified

for everybody else.

Exit Customs, and Workarounds

Obviously, an airport’s PPR/PNR requirements will vary according to where you

are arriving from, or departing to. Within Schengen, Customs are not required…

except in Greece, Switzerland, and some other “reluctant Schengen”

countries where one must still use a Port of Entry airport which in effect means

…. Customs! You have to sort this out before flying there (as described above)

but you will face it again when departing, because most countries impose exit

Customs. This is where it gets interesting…

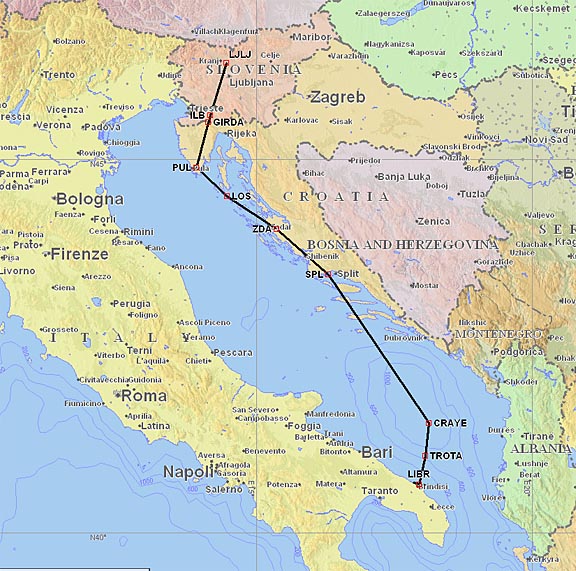

Example: you are in Brindisi LIBR (Italy, Schengen). You want to fly to Pula

LDPL (Croatia, non-Schengen). Assume that Brindisi (I’ve never been there myself)

has “Customs PNR 12hrs” then you cannot depart without having given

this 12hr notice. But if you file the flight plan for Ljubljana LJLJ (Slovenia,

Schengen) which is just up the road from Pula, you can depart immediately…

It doesn’t take a PhD to work out a solution: file a flight plan for Ljubljana

and, once out of Italian airspace, divert to Pula. To make it even more “proper”

you file Pula as the alternate, and of course you contact them first to make

sure they are open, etc. A completely plausible and very scenic route to Slovenia

passes directly over Pula (the PUL VOR):

LIBR TROTA A48 CRAYE B9 SPL L607 ZDA N606 PUL L141 ILB LJLJ

Pula will have plenty of advance notice of your arrival, starting with Dubrovnik

Radar.

Another example concerning a particular airport is San Sebastian (Spain). There,

“Customs” involves two different kinds of police officer, of which

one turns up for work and the other one doesn’t. Consequently, San Sebastian

no longer supports non-Schengen flights (in or out) even though it lists “Customs”

in the airport data. So, if needing to fly to the UK, one could file for Le

Touquet (France) and then divert to Lydd (UK).

The above techniques have been known for a long time but they breach the Customs

regulations of the departing country and should be used in difficult situations

only, where the departure airport staff is screwing you around and where you

are not planning to return to that airport anytime soon. It is a useful tool

to have in your toolbox. The departure airport will know – if they actually

care – where you really landed, from the AFTN message they receive after your

landing, but a Pilot in Command is entitled to divert due to weather, unexpected

headwind reducing the fuel reserve, etc. It goes without saying that everyone

on board still needs to be 100% legitimate for the actual flight i.e. carry

the correct passports, visas, etc because diverted flights draw extra attention

after landing.

I would also not use this technique for a departure from an airport which does

not have Customs at all, because it will be obvious to everybody down the route

that you could not have possibly cleared Customs at the departure airport.

Doing things the other way around (avoiding Customs at a destination, by pretending

to have departed from a different airport) is completely illegal and should

never be considered.

Over the years, countless UK pilots have flown (mainly inadvertently) from

non-Customs airfields in France back to the UK and I have never heard of any

fallout, but it should not be attempted because the illegality of such a flight

will be obvious to anybody who sees the filed flight plan, so you could get

picked up well before you get airborne. Flying in the opposite direction – from

the UK to a non-Customs airport in Europe – is a very bad idea too. I have heard

some distressing (true) stories of pilots who were denied landing clearances

(in Germany) despite reporting a fuel emergency, though this is equally (a)

a failure by a pilot to plan alternates; (b) a failure by a pilot to do his

job and declare a Mayday; (c) a rare example (in northern Europe) of idiotic

ATC.

In the above notes, I use “Customs” generically to refer to both

“Customs” and “Immigration” which are in theory handled

by different police forces. For example, the UK has exit Customs but

no exit Immigration.

Diverting to a PPR, Customs PNR, or no-Customs Airport

This is a legal grey area. In northern Europe, it is almost never an issue.

I recall only one case of some UK grass airfield (non ATC) refusing a landing

to a foreign inbound flight, but they did not have the right to do that except

on grounds of a lack of PPR to land on private property. There are southern

European airports which will definitely refuse a landing clearance, however,

and very occassionally an airport issues a notam saying it is closed to GA and

cannot be filed as an alternate (Corfu LGKR has done that).

Doing things properly, you should make sure your filed alternate(s) can be

flown to as a main destination, and that includes PPR/PNR. Also check

avgas availability; landing somewhere and then having to get a 200 litre drum

transported there is going to cost about £1000.

Obviously an emergency (a Mayday radio call) is OK everywhere.

A diversion away from a Customs airport to a remote strip can be expected to

result in serious police attention, for obvious reasons.

Long Distance VFR Touring in France

The standard VFR procedure is to plan a route outside controlled airspace (CAS),

but there are many scenarios where flying in CAS yields a much better routing.

Also, most VFR flights done “VMC on top” will requires a CAS transit,

due to the higher level.

France offers a particularly neat solution for higher level flight, in the

form of extensive Class E airspace. This has a base of (usually) FL065 and extends

to FL115. Within this airspace, VFR flight is unrestricted as Class E is not

CAS for VFR. UK pilots often refer to these routes as “airways” which

is misleading because it invokes comparisons with the UK airway system which

is nearly all in Class A and thus closed to VFR.

The following French SIA chart section (click on it to see an enlarged version)

shows an airway R10 from the BTZ VOR (bottom left) to the SAU VOR (top right).

This airway is also marked FL065 and this is the lowest level at which one can

fly it and clear the various obstructions

This is a great way to fly long distances in France. They are ideal for VMC-on-top

VFR touring (which a holder of a UK issued PPL can do if he has an IMC Rating

or an IR) but you need to make sure (by being conservative with the weather)

that you don’t get trapped above a solid overcast at the destination…

Airfield Movement Precautions

Taxiing around is one of the most risky parts of flying!

I am not talking about getting lost (which happens routinely to the best pilots

– you need to have the map ready and 100% sorted before starting up, and not

be afraid of asking ATC if in any way unsure); I am referring to damage to aircraft;

yours or somebody else’s. It is easy to ding somebody’s wingtip and the damage

is easily into 4 digits or more; if in any doubt regarding the clearance, shut

down, keys out of the ignition, towbar out, and move the aircraft by hand, with

somebody watching. If this annoys somebody behind you, ignore them… unlike

you, they are almost certainly renters and they can walk away from damage.

The other risk is prop strikes. This is a much bigger problem than most will

admit; anybody who “hangs around” a hangar or an airfield will see

loads of damaged aircraft. Bent blades are a daily routine in prop overhaul

shops, and each one of these is (or should be; that’s another story)

accompanied by an expensive engine strip-down to check for cracks etc. There

is a general culture among GA airfields that the airfield is not responsible

for anything whatsoever, leaving the pilot/owner to claim from his own insurance.

Many of them will only grudgingly fill in potholes, or sweep away rocks lying

on the runway. To be fair to them, many and especially the small grass ones,

are run on a shoestring and a general acceptance of liability for potholes etc

would open the floodgates. I had a £20000 lesson in this area, with a

brand new aircraft which had 1hr on the clock…

Grass airfields often have potholes, or undulations which can cause the prop

to contact the ground, and some hard airfields have concrete/grass transitions

where the step causes the suspension to dip enough for the prop to hit. Hard

airfields also often have stones which cause dings in the prop. Such dings need

to be “dressed” (basically, filed out to make a new smooth leading

edge) which cannot be (legally) done by a pilot, but the removed metal will

eventually lead to an out of balance prop which will need to be dynamically

balanced – £300 plus. On the next prop overhaul, the blade edge has to

be restored all the way along its length and once the amount of metal removed

reaches a specified value, the blade has to be replaced, which for balance reasons

means replacing all blades, which usually means a new prop as the only economic

solution, so basically you have just paid £10000 for years’ worth of operations

in airfields where nobody was bothered to use a broom.

The best precautions are: Upon arrival, if visiting, always ask ATC for a hard

surface parking. They may not have any but it is always worth a try. Before

departure, walk around the aircraft and walk up the likely taxi path leading

away from the parked position, checking for potholes, and picking up any stones

bigger than about 1cm. If there is a grass/concrete transition nearby, inspect

it for the best point at which to cross it, and cross it at an angle of say

45 degrees. When taxiing, the visibility of hazards ahead will be limited but

if you see Apollo-sized rocks lying on the taxiway (historically, Elstree EGTR

had one of the finest collections of these, until the CAA shut it down until

they did something) then get up a bit of speed before you get to them, and idle

the engine when driving over the top, to minimise the chance of the prop sucking

them up.

The above advice is not over the top. In one case I know of personally,

a renter started up with the towbar still in place, took a 20 × 20mm chunk out

of a blade, threw the bent towbar away where it would not be found, went for

a flight, came back and said nothing… and vanished. If you are an aircraft

owner, this is the kind of “diligent” culture you will encounter in

some places. So if in any doubt, as I say above, stop, get out, and use

the towbar.

Cold Weather Operations

There are two distinct issues: removing frost before a flight, and fuel icing

during a high altitude flight.

Removing frost can be a way of life during the winter, if parked outdoors

overnight. Water from a tap can be usable for very marginally-freezing conditions

(e.g. where the temperature is already rising through 0C) but is usually ineffective

because the large cold fuel mass in the wings causes it to simply freeze on

the wings, regardless of how much is available. It also runs the danger of freezing

up control surface bearings or even linkages, in some types of aircraft. So

a de-icing fluid needs to be used, and obviously it needs to be stuff which

is safe on aluminium, the windows, etc.

There is a lot of “street knowledge” on which cheap fluid is supposedly

OK, but one must always remember that most pilots are not owners and will not

become aware of long term damage. Most owners use the proper aviation stuff,

which is not cheap unless one can mix up something which is definitely equivalent.

The most obvious stuff is the TKS de-ice fluid which can be purchased (UK) from

e.g. Silmid as Aeroshell

07. Kilfrost is another

supplier, with slightly better pricing (for Type 1 de-icing fluid). It is very

expensive; nearly £200 including delivery for a 20 litre drum.

Frost can also be scraped off with e.g. a credit card but this will damage

the aircraft finish, especially windows.

Aeroshell 07 is also the fluid used in TKS anit-ice systems. The high cost

is irrelevant on a prop-only system but is an issue on the full system which

can use up the whole lot on one flight in IMC. Also, in Europe, one has the

same issues as with oxygen in that hardly any airports provide a top-up facility,

and most owners keep a drum back in their hangar.On long trips I carry a 2 litre

topup bottle of the TKS fluid, which is just the right amount for completely

refilling the 2 litre prop TKS fluid reservoir. For safe leak-proof carriage

of this stuff I use HDPE (high density polypropylene) 2 litre bottles which

can be bought cheaply from laboratory suppliers e.g. here

(local copy). These HDPE bottles can also be

used to carry IPA – below.

Fuel icing is a highly aircraft type specific phenomenon. In normal

N European temperatures is almost unknown on the common training types but that

could be because almost none of them get to fly very high. The Piper Aztec has

been reported as severely susceptible to it at any OAT below about -15C. My

TB20 does not appear to have had any reported cases. The standard precaution

is to add some IPA (isopropyl alcohol) or Prist

to the fuel, during refuelling. IPA is safe and cheap but the required concentration

can be up to 2% which means that on a very long trip one has to carry rather

a lot of it, which is why some people use the more effective (and carcinogenic)

additives like Prist which can be added in much smaller amounts.

Airborne

Flying is the easy part of aviation!

The most straightforward procedure is if the entire flight is in controlled

airspace. You collect the departure clearance (from the Ground, Tower, or Clearance

Delivery frequency; there seems to be no obvious rule) and this contains the

SID, squawk code, etc. For a VFR flight, the SID will be replaced by some departure

instructions; usually a low level flight to some VRP.

The SID is the lateral clearance; ATC will advise the vertical

clearance before departure, and it is important to realise these two are totally

separate clearances in all phases of IFR flight – except when “cleared

for XXX approach” at which point you are authorised to immediately descend,

at the highest rate of descent of your choice, to the published platform altitude

for that approach.

Getting the paperwork right is important. Make sure you have all the SIDs ready,

and also the approaches in case you need to make an emergency return. The simplest

thing – the airport map – is vital and you need to suss out where you are parked,

before calling up for the taxi clearance.

Most airports don’t care if you start a piston engine without a startup clearance,

and at many of them the tower cannot see the GA parking area anyway. But some

do get funny about it, so it is always good to “request start” just

in case.

For an airfield outside controlled airspace, a provisional IFR departure clearance

(not really a “clearance” as such because nobody has the power to

issue a clearance outside controlled airspace) is collected either from the

tower or from the regional FIS unit (in the UK, usually London Information).

On flights filed for a decisive airways level, say FL100+, the next unit to

speak to will be London Control, and they will usually issue rapid climb instructions

to the filed level. But you don’t want to fly into something nasty while obeying

the instruction, so if there is some convective weather around, a good trick

is to climb as far and as high as one can in an appropriate direction before

calling up London Control.

One odd thing I have found is that some airports peripheral to big cities use

not only their own published SIDs but also SIDs belonging to other nearby airports;

for example Pontoise uses some SIDs published for Le Bourget. This is mentioned

as an obscure one-liner in the Pontoise AIP…

Maintaining one’s IFR clearance: Just because a route is accepted

by the Eurocontrol computer does not mean that ATC will operate it in the air

as a fully IFR flight. One can file an “IFR” route, hundreds of miles

long, at 2000ft, but since all or part of it will be outside controlled airspace

(CAS), UK/European ATC will not provide an IFR service on the flight. 2000ft

is an extreme example, but it is easy to file a route at e.g. FL070 which is

“dropped” by ATC because it has departed CAS at some point. And it

can happen at higher levels. It can also happen for other reasons e.g. when

flying from France to the UK, below FL120, one can get “dropped” because

the French unit does not have a handover agreement with the UK unit. It is difficult

to establish the exact limits for this but it remains a persistent problem for

IFR pilots wishing to fly at sub-oxygen levels. Leaving France at FL120+ appears

to solve it (through being handled by Paris Control, which can hand over directly

to London Control) as would flying along certain routes such as ORTAC-SAM. More

recently (8/2010) it has become apparent that one can stay with Paris Control

at lower levels too, e.g. FL100.

Oxygen is highly desirable. It is a legal requirement above

11000-12500ft (the actual figure depends on the State of Registry of the aircraft)

but its use anywhere above about 8000ft makes a huge difference to how tired

one is upon arrival. Some people are significantly affected above about 11000ft,

especially at night. Subject to aircraft performance, it enables a climb above

the clouds, out of icing and turbulence, and being able to file at FL140+ often

yields much better routings than at say FL100. Oxygen is one of the greatest

“secrets” of IFR flight, and the equipment

can be obtained relatively cheaply in a portable form.

Airborne collection of IFR Clearance, following a VFR departure

This can be a particularly dangerous phase of the flight, and one needs to

have a clear “plan” for what to do if there is a delay in getting

it.

The strategy depends a lot on the kind of airspace in the vicinity of the departure

airfield, and weather.

If there is no CAS nearby, in the direction of the flight, and the weather

is very clear, then one can simply commence the flight and sort out the IFR

clearance whenever it gets sorted out. An example of this is a departure from

one of the UK south coast airfields, when the tower is unmanned; in this case

the first contact is London Information who are supposed to provide an FIS while

waiting for the transfer to London Control for the proper IFR service. It is

common for London Information to take 10-30 minutes to do this, during which

time one has flown quite a distance, and it is obviously helpful if the distance

flown is in the general direction where one wants to go! So departures to the

south, east or west are usually OK (ones to the south often result in you being

in French airspace before London Control come back) but ones to the north cause

you to be trapped at low level under the LTMA, with no chance of a climb due

to the Gatwick/Heathrow flight paths.

If there is CAS nearby, it can get tricky. I recall this

departure from Messalonghi in Greece, where an IFR clearance was never formally

obtained and, as far as I could tell, the flight remained in limbo (VFR or IFR?)

until I landed at Corfu LGKR. Now combine this with some terrain and poor visibility…

In the extensive UK Class G airspace you can just drive straight into IMC without

talking to anybody but in most countries it is illegal to enter IMC without

an IFR clearance (notwithstanding the fact that nobody can give you a clearance

for anything when outside CAS) or, to put it more generally, it it illegal to

fly IFR outside CAS. Nevertheless pilots do get killed while fumbling around

in the air, calling up various frequencies, or simply waiting for an IFR clearance,

while trying to stay clear of terrain, in or out of VMC… It may be better

to stay on the ground until the weather improves. In some countries one can

pick up an IFR clearance pre-departure, with a phone call, which is a great

solution, but this is rare in Europe.

There may be “weather” in the departure area in the intended direction

of flight, but not in some other direction. In that case, a useful trick is

to depart in the latter direction and climb right up to the base of CAS, before

calling up anybody for the IFR clearance. This may enable you to get above the

clouds, where one can size up the conditions a lot better than from the ground.

The worst case scenario is a departure from an airfield which one cannot safely

return to due to low cloud, followed by an inability to get the IFR clearance…

the “inability” could be a radio failure, or terrain masking of VHF

comms. This is why any pilot doing this sort of flying should have a GPS running

a real topographical map of the area, or at least an electronic version of the

“real printed” VFR chart. Total 100% terrain awareness is a must.

After Landing

If refuelling, always refuel immediately after landing. In most situations,

one has a bit of time at that point – more time than one usually has when departing.

But the biggest reason is that most airports are dead keen to get you off the

airside ASAP, for “security” reasons. “Security” is a wonderful

empire building catalyst and this is a job which even the most disorganised

airport can do. If you refuse to leave the aircraft until avgas turns up, avgas

will turn up far quicker than it would do otherwise. Commonly, a van turns up

within minutes of parking up; if you tell the driver you need avgas now

then he will make the right calls to the right people, fast.

If staying for a known period, try to also pay all fees after landing, for

the same reason.

This one will sound really obvious: on your way out through the terminal building,

find out exactly what you need to do to get back in, to pay for stuff, and to

get out to the aircraft. Some quite sizeable European airports are practically

deserted – except for the cleaners, who won’t speak English – and the whole

place comes alive, briefly, a couple of hours before the Ryanair flight is due…

I have spent an hour at Bastia (Corsica) and Zaragoza (Spain) trying to find

someone who could speak English enough to understand “general aviation”,

and that included the Tourist Information desk staff at Zaragoza. Obviously,

this is where mobile internet really helps because you don’t have to mess around

filing flight plans, etc. But if you depart without paying every last penny

(which in some places e.g. Corfu means going to several different offices) the

airfield will pursue you, which can cause considerable hassle if they

don’t have your name and address.

Avoidance of Handling

Most GA pilots regard avoidance of handling (or “self handling”)

as the Holy

Grail; unsuprising given the usual silly costs. It is not unusual to find

a big airport where the landing fee is say £50 but the handling inflates

this to £150. In most cases, for light GA users, handling offers next

to nothing for the money.

If handling is “non-mandatory” then it usually won’t be offered (to

piston GA) but can anyway be avoided by refusing any offers of handling.

If handling is “mandatory” then it can usually be avoided by visiting

a local flying club or a business based at the airport. Oviously the latter

tactics need a prior arrangement with the club/business; you cannot just park

up at some maintenance company and walk off. The intention to park at the specified

establishment needs to be passed to ATC immediately after landing. At “mandatory

handling” airports, the handling agents are wise to this revenue-reducing

practice and may press you for details of what “maintenance” you are

having done…

The top-priced airports (e.g. Gatwick, Frankfurt, Munich) whose total costs

are in the £400 region are all “mandatory handling”, as far

as I can tell. The landing fee is only about 1/4 of the total cost. The handling

agents (e.g. Harrods Handling) are wonderful and exceedingly posh, employing

the world’s supply of well dressed women, but as a light GA user you are just

paying £300 for free coffee and fresh croissants. This whole business

is propped up by business jets whose owners don’t care what it costs, and by

airport management which cannot be bothered to make a provision for light GA.

However, handling agents do have their uses. At many airports, the handling

agent is the only bit that is run in a proper businesslike manner. They have

the right connections around the airport and can usually instantly arrange PPR/PNR

and one phone call to the agent can be all that one needs to do prior to flying

there. Prior to departure, the agent should produce a customised weather briefing

and take care of filing a valid Eurocontrol flight plan; these functions are

much less relevant these days, but if you are in a hurry to get away, it is

an option. The handler is also much more likely to speak English than airport

staff. This is how aviation is “supposed” to work – worldwide – and

it is only piston GA pilots who keep trying to circumvent the system, to save

money…

At certain more southerly European airports, the handling agent will use a

part of his fee to “lubricate” the right people to ensure that an

“impossible” parking space magically appears. Outside Europe, this

kind of thing is much more overt and regulars tend to carry wads of US dollars,

etc for paying bribes to various officials.

Unsuprisingly, handling is the normal way of doing things at the business jet

level, because a lot of the flights are done at short notice and nobody has

the time to mess around sorting out PPR, in-flight passenger refreshments, etc.

At the top end of the piston GA scene, there are pilots who prefer the comfort

of a handling agent. If using a handler, try to use one with a permanent base

on the airport; these can often be identified by the presence of a discrete

radio frequency in the ACUKWIK listing.

In the EU, mandatory handling is reportedly illegal unless there are at least

two agents to choose from. In practice this makes little difference because

they simply agree to set similar prices…

Avgas Duty Reclaim

In most of Europe it is possible to get fuel free of duty (taxes) and VAT,

on production of an AOC. However, an EU

regulation (local copy) mandates duty free

fuel for non-private operations, so the suggestions in the aforementioned link

may be worth exploring.

In the UK, one can reclaim duty on fuel that has been exported. This highly

valuable concession is called the Duty Drawback and currently (2012) is worth

about 40% of the fuel cost! Under this concession you can claim for the entire

content of the fuel tanks, even if the foreign trip was brief; it works on a

principle similar to airport duty free shopping where you can obviously bring

the duty free goods straight back to the UK. Obviously, the fuel claimed for

cannot be claimed for twice… so some administration is required to make sure

this does not happen.

Payment Methods

This used to be an issue, necessitating the carriage of Visa, Mastercard, AIR

BP and other fuel cards, and plenty of cash, but I have seen a big improvement

over the past few years. Today, a Visa card works at nearly every manned airport.

I still have an AIR BP card and always try to use it, but most airports do not

accept it. One apparent exception was Lelystad where it was the only apparent

means of payment on the self-service fuel pump, but in fact the airport office

– when staffed – was able to get around this.

France has many small airfields with self-service pumps, which require the

TOTAL fuel card but this requires a French bank account – a load of hassle for

most people. Fortunately most of these airfields are non-Customs and thus unlikely

to be visited by an internationally travelling pilot.

Aircraft Ownership

This is a vast topic so I will mention just a few general points that are applicable

to the owner of an ICAO certified aircraft.

For an aircraft owner, maintenance is the biggest learning curve, largely because

most of the GA maintenance business is geared up to make money on the back of

the lowest common denominator: owners looking for the cheapest legal job; many

of these are flying schools. And there is a vast range of practices that go

on. With most of these – dodgy lubrication being the main one – the culprit

is untraceable except via increased airframe maintenance costs years later.

As a result, piston aircraft ownership is not like owning a BMW, which you can

take to any BMW dealer and get a reasonable job done – most of the time.

Speak to other owners and find out where they get their maintenance done. Having

found a company which comes with reasonable recommendations, you need to get

pro-active and be involved in maintenance – even if a Part M company is “in

charge” of it nominally.

Get hold of the maintenance manual for the aircraft. These are often expensive;

some manufacturers have sold the rights to a U.S. firm called ATP who sell a

CD based subscription for about $1000/year. Each month’s CD is supposed to go

in the bin when the new one comes out, but except on current aircraft types

very little changes from one year to the next and the out of date CDs make a

great educational reference. Sometimes they appear on Ebay…

One learns a tiny bit about how airplanes work in the PPL but this is nowhere

near enough.

Many owners will prefer to leave everything to their maintenance company –

this is OK if you have a good one.

If you are buying into a group (a syndicate) then meet all the members and

see how well you get on with them, etc. They will no doubt be polite to you

because – at best – they don’t want to obstruct the sale of the share or – worse

– they are keen to see the back of a troublesome member, so you need to go beyond

that and check out what kind of flying they like to do, what they do for a living,

their flying patterns, etc. The group members need to be well matched in their

ability to fund unscheduled maintenance, in their attitude to VFR v. IFR (a

mostly-VFR group will not be keen to replace failed IFR avionics, forcing IFR-capable

members to jump ship), and in their flying patterns (some groups have a dominant

member who does a lot of hours). Ask about their duty drawback policy; some

groups allow the entire drawback to be pocketed by the pilot flying abroad,

which means his overseas trip has been subsidised by the others. Ask who is

in charge of stuff like insurance, and deciding what “optional” stuff

gets fixed during maintenance. Some groups work very well but they tend to be

either small groups comprising of well matched members, or large groups which

provide cheap casual flying but have a dedicated “manager” who does

all the admin.

Photographs

One of the biggest attractions of flying is the potentially great scenery.

Unfortunately, it is not always easy to get acceptable photographs. The biggest

problem seems to be reflections from surfaces and objects inside the cockpit;

other issues include: the camera focusing on the window and not outside; poor

contrast; poor focus.

The most effective way to avoid reflections is to hold the camera close to

the window surface – but not touch the window as that transmits high frequency

vibration to the camera which blurs the picture. A simple method is to press

one finger (A) of the hand holding the camera against the window; this stabilises

the camera while making it possible to maintain a small gap (B) between the

camera and the window:

The relevant area of the window should be clean and scratch-free, otherwise

the contrast is poor and the camera may autofocus on the scratches instead.

If a clean window is not an option, make sure the camera is set to manual

focus and is focused on infinity. This can be tricky to do exactly because on

most lenses true infinity focus is not quite on the “infinity” stop…

In general, use the smallest available F-number as this minimises the effect

of a bad window.

If reflections remain, identify the object causing them and relocate it, or

cover it up. Often, the bright papers on the kneeboard are the cause; turn the

kneeboard upside down. In extreme cases, use a piece of a black cloth to cover

up the offending item.

If possible, take pictures out of a window opposite to where the sun is shining

i.e. try to fly to the south (northern hemisphere assumed) of the object being

photographed.

Formation photography requires additional tricks. Obviously, one must avoid

a collision and various well tried methods exist for this. I tend to ensure

separation by well spaced departures and climbs to pre-arranged altitudes, separated

by 500-1000ft, with the later-departing aircraft climbing to the lower altitude,

to a GPS waypoint at which one can orbit until visual contact with the other

aircraft is acquired. Then, one can fly parallel tracks and get the photos.

As above, use the sun to your advantage by having the camera aircraft flying

on the south side of the other one.

There appears to be a consensus that the most attractive photos of another

aircraft are those which show about 20-30 degrees of the propeller blade’s rotation

which implies a shutter speed of around 1/160 to 1/250 – much slower than the

1/1000 or so normally used in bright conditions with an ISO100 camera. This

requires a steady hand and – if the other aircraft is doing a fly-by – panning

of the camera. Shooting at 1/2000 or so produces a frozen propeller which is

unattractive.

A good article on the above is here.

Obviously, safety is vital and a second person is highly desirable in the camera

aircraft – to take the pictures and to keep a lookout. An autopilot is extremely

handy…

Finally, a reasonably good camera makes a big difference. Most of the sub-£200

compacts, and all phone cameras, are of poor quality – even if the resolution

is 10M pixels or more – because their lenses are so small. However, you don’t

need to be equipped like an F16 plane spotter in Greece to get very good pics;

there are pocket-sized cameras whose optics are just that bit bigger and a lot

better. The Canon

S90 (or the later S95) is perhaps the best pocket-sized camera at present;

this pic was taken with it.

Many airborne pics are spoilt by haze, which in southern Europe can be present

even at high altitudes (above 10,000 feet). There is nothing that can be done

about it with filters, but adjusting the Levels in Photoshop manually (adjusting

R,G, and B separately) [detail needed here] usually produces a good result.

Filters are rarely used with modern digital cameras. They were routinely used

with film to match the colour temperature of the light source to the fixed spectral

response of the film, but a digital camera has a user setting for the colour

temperature so a filter is pointless. However a circular polarising filter works

very well in eliminating reflections and glare from water and it enhances colours.

Unfortunately, to get the right effect, it needs to be rotated for each shot;

you can’t just screw it on and shoot away in all different directions.

If shooting through a propeller, there are two ways to get rid of the prop

blade(s): take many pics and hope that you eventually get a clean one (which

works a lot better with a 2-blade prop than with a 3-blade one), and use a slow

shutter speed of about 1/60 or slower.

Most of the above notes apply equally to movie cameras, but these have

their own issues if shooting through a propeller. All the compact “webcam”

or “bullet” cameras (I tried quite a few) suffer badly from this because

they don’t have an iris; they use the electronic shutter alone to control exposure,

and in most daylight situations the shutter speed ends up being far too fast

to properly blur the propeller. My experiments have shown that a shutter speed

or around 1/120 (or slower) is needed to eliminate the prop effects. Unfortunately

few cameras below £1000 have any user configuration for the shutter speed.

The excellent Canon

HF-G10, at over £1000, is one of the cheapest ones which has a shutter

priority manual mode. Where no user setting is available, one can try a neutral

density filter to reduce the incoming light and to force a slower shutter speed,

but this rarely solves it thoroughly. I tried some pretty heavy neutral density

filters with a Sony HCR-HC1E (£1500 when new in 2006) and they did very

little…

[more to do]

Last edited 4th August 2012

Any feedback, reports of dead links, corrections or suggestions much appreciated

Contact details